Photography has been tied to the objectification and categorization of criminals since its inception. In 1888, the French biometrics researcher Alphonse Bertillon invented what is now referred to as the mugshot. Seen as an institutional tool for documenting criminals to assist in victim identification and police investigation, mugshots have over the years developed cult appeal. An article in the New York Times entitled “Mugged by Mugshots” exposes a for-profit industry of posting mugshots online. “It was only a matter of time before the Internet started to monetize humiliation.” The fact that mugshots have little to do with a subject’s guilt or innocence is beside the point. Guilt is presumed, the aesthetics alone are damning.

Making money off of supposed criminal humiliation is only part of the story; prisons are also ‘for-profit’ in this country making it increasingly difficult to reform the broken system that is making so much money for so many. What is fair to say is that in a system where your financial status is the most reliable factor in ascertaining your likelihood of becoming a convicted criminal, justice has little to do with it.

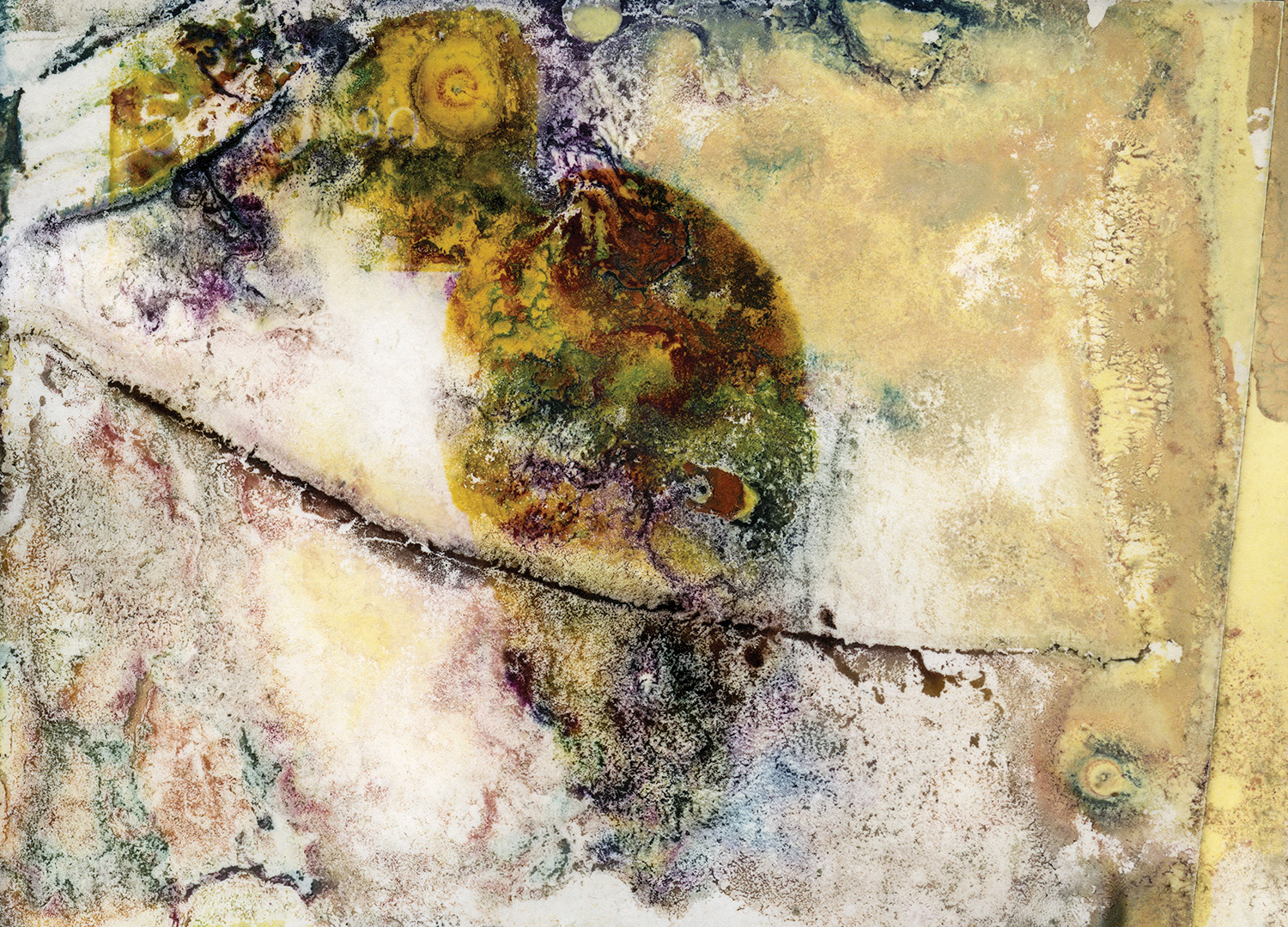

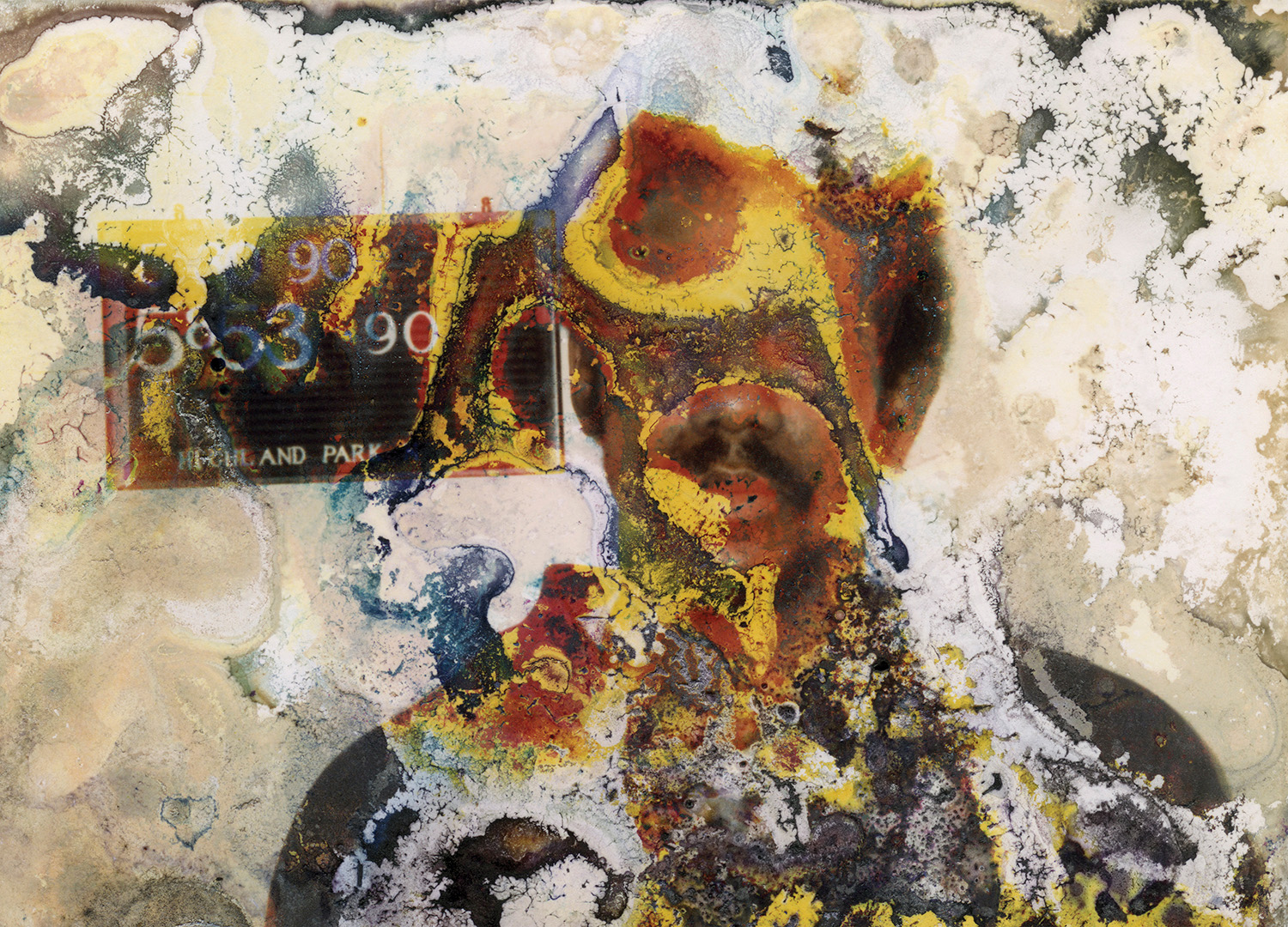

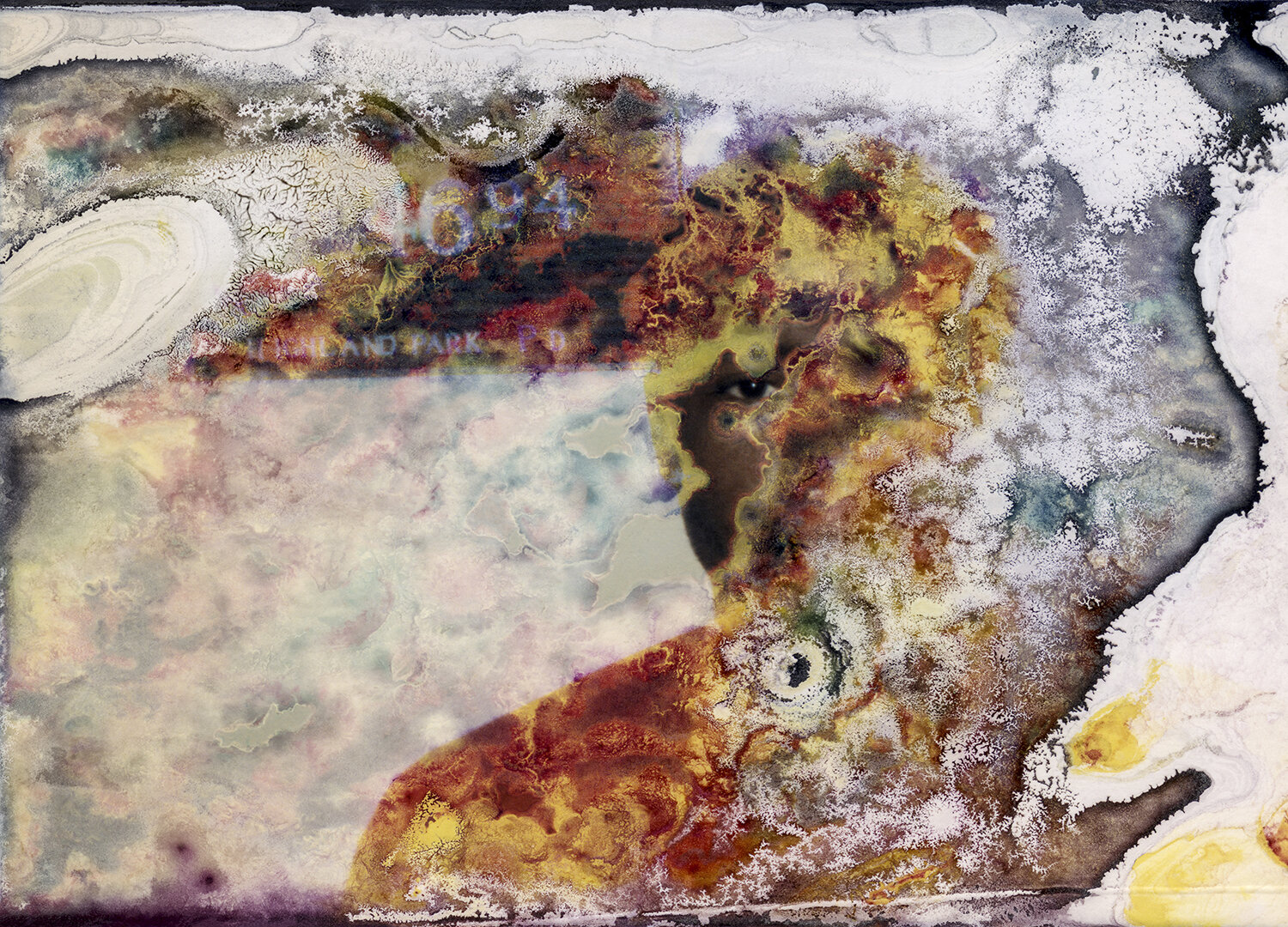

In an abandoned police station in Detroit I found a cache of mugshots that had been left for years to weather the storm of destruction and decay that has plagued that city. They serve as a counterpoint to the fetishization of mugshots. In these images the individuals are no longer being recriminalized, rather they are absorbed into the larger narrative of a place that criminalized them. These photographs are part of a physical and chemical collapse, which now obscures the very thing they were created to preserve, the identity of the accused. Many are no longer recognizable as criminal portraiture at all. They speak now of topographic aerial views, landscapes and impressionism, color fields and peeling paint.

These mugshots are evidence of the breakdown of the photograph, the city of Detroit, and of the United States Criminal Justice System. They speak of what has happened to the city as a whole and they have also returned to what they always were, an idea of criminality that bears little or no resemblance to concrete realities, Criminal Abstractions. If, as Eula Biss suggests, “there is always some promise in destruction,” then perhaps Detroit, and these mugshots, are proof of that.